Viva Las Vegas - Part 3: Learning from Shanghai?

To finish out the posts on my reinvestigation of Las Vegas, I’m concluding with perhaps the most significant development on The Strip since the 1990s. And that’s been the very deliberate (and very expensive, and likely very profitable) rebranding of Sin Sity as a true urban landscape, a “destination city.” This seems to be in order appeal to a more international (and largely affluent, quite Chinese) tourist audience.

In short, Las Vegas is Learning from Shanghai.

My pun refers, of course, to the rather famous study by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour in which they asked the architectural community what might be learned from studying the design of the Las Vegas Strip. And Vegas has learned, to. Once it was from Disney. But that era (1985–1995 at its peak, with thematic rumblings well into the 00s) appears to be winding down.

At the heart of this new rebrand is CityCenter.

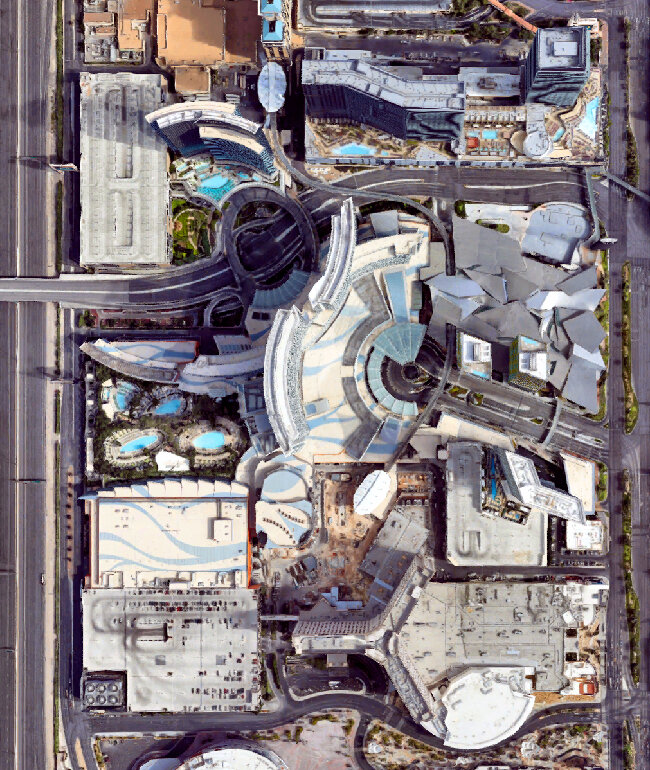

CityCenter under construction, July 2008.

The prior time I had conducted site research in the summer of 2008, construction was well underway. The final price tag for this 76 acre, mixed-use urban complex was about $9.2 billion, making it the largest privately funded construction project in U.S. history, Fittingly, Walt Disney World once held that title.

CityCenter under construction, July 2008.

Seeing those towers arise out of The Strip, surrounded by all the other themed casinos struck me as super surreal. At first it felt like just another theme, as if this was a Blade Runner (1982) techno future kind of thing.

CityCenter under construction, July 2008.

A kind of future, certainly. Managed by AECOM Tishman, the project was a collaboration between eight world-renowned architects and MGM Mirage (now MGM Resorts International) and is the largest LEED-certified project in the world (six Gold certifications). But also, like Blade Runner itself, it represents something of a dystopia.

For example, the rounded tower being built above no longer exists. Very serious construction defects in The Harmon were discovered that year I visited, and work stopped. The tower was deemed unsalvageable; they started tearing it town in the summer of 2014 and a little over a year later it was gone.

CityCenter under construction, July 2008.

The CityCenter project could not have opened at a worse time. When it was announced in 2004, things looked great. Then global economy tanked in the fall of 2008, and the response when doors swung open in December, 2009 was a collective yawn (and, in investor circles, a whole lot of sweating).

MGM’s initial financial partner during the construction phase was Dubai World, who was also racked by the Great Recession. However, things are now on the mend. Just this summer, MGM announced they were buying out Dubai World’s stake (to the tune of over $2.1 billion), giving them full ownership of the Aria and Vdara resorts on the property. MGM then plans to sell the hotels off, and lease them, turning a longer-term profit on their investment.

It looks almost like a model, doesn’t it? Or a CGI background from a sci-fi streaming series. When initially pitched, the project was described by MGM as a “self-contained city-within-a-city.” Walking around deep inside, looking up at only modern skyscrapers, it certainly felt that way. Like being inside a Disney park surrounded by an earthen berm, you can’t see the rest of Las Vegas outside CityCenter.

The dystopian Detroit of 1987’s Robocop was also fresh in my mind. Concrete and steel, abstract and angular. Almost a postmodern take on brutalism. It’s so out there, and so not what I expect from Las Vegas.

I won’t digress too much here into cinematic subsumption, which I’ve blogged about before and also have expounded upon in scholarly journals [here] and [here] with my writing partner Greg Turner-Rahman. But basically, the built environment (and by extension, our very lives) has been completely colonized (or “subsumed”) by the language of cinema. I’ve mentioned feeling like CityCenter is Blade Runner or Robocop. Looking up at this particular building, all I could think about was The Towering Inferno (1974). This is an aside, but I’ll be returning to it in future posts: movies change the way we experience the built environment.

So who was this Postmodern Sci-Fi Future Tech City built for? It wasn’t movie fans. As Stefan Al describes it in his fantastic The Strip: Las Vegas and the Architecture of the American Dream, this new approach is what he calls “Cosmopolitanism” and it’s aimed squarely at the international leisure class.

Al notes that this began with the opening of The Palazzo in 2007, a tower expansion of the more traditionally themed Venetian Resort. Here the design departed from a literal approach:

In Las Vegas, replica buildings had lost their luster, so [owner Sheldon] Adelson changed the name to the more generic Palazzo. Instead of a classic Venetian style, it was going to be a modern interpretation of Italian Renaissance like the one that was so pervasive in Southern California’s high-end shops and McMansions. “The Palazzo won’t have a recognizable theme like the Venetian.” a Las Vegas Sans spokesman said, “but instead will be an upscale design reminiscent of Bel Air, Rodeo Drive and Beverly Hills.”

The aesthetic broke free, in other words, from the more Disney approach of immersing guests in a recognizable setting of time and place. Renaissance Italy became a more generic “Southern California Luxury” that relies on international brands connoting a particular lifestyle and a certain class of people.

And so it is at CityCenter (a name MGM retired in 2015, preferring its Aria brand). This is supposed to feel like staying the night (or the week) at any other luxury-level site from Shanghai to Paris, Berlin to New York City. The hotels, entertainment, restaurants, and indeed the architecture itself are meant to provide—as MGM had initially promised—the feeling of a “city within a city.”

The integration of DNA from numerous global luxury brands is far from subtle, too. This mall could exist in any one of a dozen cities around the world. But it’s bolder. And in the afternoon I spent walking around, the customers were anything but American (I guessed maybe one in three were from the U.S.). There were many Europeans and, predominantly, visitors from Asia.

Even some old chestnuts have been imported in to provide some pixie dust from other well known destinations with hospitality heritage. The very name Waldorf Astoria provides credibility to those who have visited in New York City (and spent their money there).

I mentioned Shanghai at the start of this post because, architecturally, that’s what I see. And inside the shops and hotel lobbies, that’s the kind of money I saw being spent. I did not see theme park families, the Florida set. I saw older, high rolling couples from other countries. And if there were children in tow, they were fully grown.

What will become of the Disneyland-style family destinations on The Strip? Once again as Al points out, Las Vegas tends to reinvent itself every twenty years or so. Will Paris and The Venetian and The Mirage and Treasure Island and New York New York and Luxor be vastly redesigned? Some are already headed that direction. The Island sunk its pirate show a ways back and is now the “TI” with a focus on sexiness. Luxor has been shedding its Ancient Egyptian roots for years.

Or will some of these be imploded completely? I could see something inexpensive and tame like Excalibur remaining for the kiddies. But for many of these other themed resorts from the 1980s and 1990s, I’m not so sure. Things get even more dicey when you consider that the majority of the casino resorts I just listed are all owned by the very same MGM Resorts.

Las Vegas has learned from Shanghai. Where it will take up studies next?